|

|

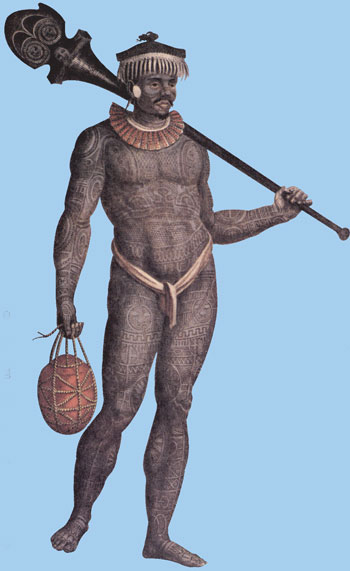

At the end of the 18th century Captain James Cook returned from his voyages of exploration in the Pacific with reports of palm-fringed beaches, rugged mountains and lush vegetation that established forever in the Western popular imagination the idea of Polynesia as paradise on earth. These seemingly idyllic islands were, however, rife with social and political unrest in which fighting was a constant and all-consuming activity. Conquest, small-group rivalries and feuds, revenge for individual slights, and the need for cannibal and sacrificial victims all were causes of violence. Since warfare was such a vital part of Polynesian life everything having to do with fighting was imbued with spiritual significance, and Polynesians devoted considerable attention to developing martial skills and manufacturing weapons. Before European contact clubs were the most effective weapons the Polynesians had at their disposal, and therefore the most favored. Because clubs were culturally so important, they developed into objects of not only deadly effectiveness but also great beauty. With stone adzes and stone and shark’s tooth chisels Polynesian artists created an amazing variety of carved and decorated clubs. After European contact, the introduction of iron nails stimulated the development of increasingly intricate and refined surface decoration. By the end of the 19th century warfare had ceased due to political changes within and among the island groups, and Western weaponry had rendered clubs obsolete except for ceremonial use. Today, the museums of the world display fine Polynesian clubs as exotic art. Polynesians see them as part of their cultural heritage and, in the Marquesas Islands and New Zealand especially, the carving traditions that produced them are alive and well. Enter the Exhibit |

||

|